The Day After television series aired on November 20th, 1983 and was watched live by almost two thirds of Americans, as many as the most popular Super Bowl games. But this cultural event wasn’t about sports. It was about the ongoing threat of nuclear war. The program is a literal piece of science fiction, distilling the dense language of government reports and figures into prime-time television. It follows the lives of a few families around Kansas City as their lives become critically changed by a nuclear attack. The show oozes Americana in the panning shots of farm buildings and corn rows. As the first alerts of trouble at the border between West and East Berlin come in, the scene toggles between the different families at the heart of the story – black, white, young and old – all in clapboard houses with shaker-style cabinets and corniced window drapery. The falling bombs change everything: within moments, the comfortable world of Middle America is replaced by an inhospitable, post-apocalyptic wasteland. The sparkling white siding and pitched shingle roofs are replaced by the concrete walls of basement levels and technical rooms. The fields are charred, grazing cattle lie scattered in the fields. Even the iconic family dog is left outside to die for want of food. A preacher, doomed to death by radiation sickness, preaches among the remnants of his church as his congregation dies in the pews. The fragility of life before the bombs is made clear by its total absence in the aftermath.

“Hope for what? What do you think is going to happen out there? You think we're going to sweep up the dead and fill in a couple of holes and build some supermarkets?”

(Excerpt from The Day After)

The central role of the home in relation to nuclear apocalypse fiction – or what I will refer to here more simply as ‘nuclear fiction’ – stems from the logic of the bomb itself. War has always involved large-scale destruction, think the apocryphal salting of the earth at Carthage by the conquering Roman armies or the scorched earth policy. Yet war between armies and monarchs, with countries changing hands from the death of a leader, was upended with the advent of the modern state. When no single person’s death can seal a victory, territory has to be taken through occupation, involving far larger numbers than the comparatively small, private armies of the past. In this context of total war, gross productive capacity for producing weapons (GDP) becomes a limiting factor of a country’s ability to defend or attack. When fighting at full capacity, large-scale levelling of productive capacity becomes an effective tool of attrition. As the opponents struggle to produce and maintain armaments they can easily be defeated. From the perspective of the aggressor, destruction also produces a secondary benefit, the ability to quickly establish ‘facts on the ground’ ownership of conquered land through reconstruction: ‘I built it, I own it.’ Throughout the world wars, larger and larger conventional bombs were used to such effect. The dropping of the nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was merely a change in scale rather than strategy, the inevitable end result of the trajectory of multiplying kilotons that brought the logic of annihilation of production to its climax. While conventional bombs could destroy factories and airfields (with varying degrees of accuracy and collateral damage) the workforce could simply be redeployed elsewhere. During the Blitz for example, the Plessey defence electronics factory was relocated to the tunnels of the Central Line in London after the original was heavily bombed. Nuclear weapons on the other hand could destroy entire built-up areas. Not just factories, but the homes and the workers who service them, are removed from play, the duration of the fallout stopping any opportunity to rebuild.

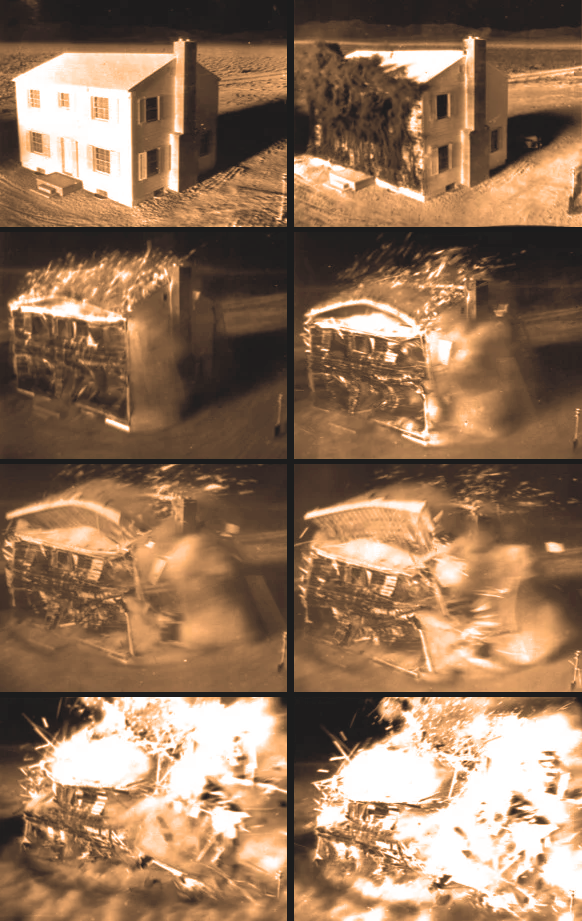

As a participant in the balancing act of mutually assured destruction, the US Government was well aware of the stakes and objectives of the bomb. It is little surprise then, that during its development of more destructive weapons, the Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA) was also testing their effects, conducting a series of research projects called Operation Doorstep. Their purpose was to investigate the factors affecting survivability for non-combatants in a nuclear blast and “to show the people of America what might be expected if an atomic burst took place over the doorsteps of our major cities”. In fact, many of the videos that came out of the operation were used during the bomb scene in The Day After, spliced together and edited alongside the director’s footage. All of the clips have a similar feel, but the first one revealed to the public in 1954, called Annie, is the most iconic. The 15-second clip portrays a stereotypical American two-storey suburban home, standing alone in the middle of the desert. One side is suddenly illuminated by an unseen light source behind the camera, casting long shadows across the desert floor. As the intensity grows the clapboard begins to char, the smoke forced up the face of the house by a rising wind. In a moment the shock wave hits and the house is blown away in a cloud of kindling and smoke, as if by a gigantic ‘huff’.

The video was recently re-released by the government in crisp HD and its effect on the viewer remains chilling, even now. The clinical feeling of the scientists’ gaze, the quickness of shot, the lack of context for the destruction, the meaninglessness. It’s no surprise then that the motif of the lone house in the wasteland seared itself into the psyche of a generation of writers. With this in mind, it’s hard not to see the last house that remains of a city in Ray Bradbury’s short story There Will Come Soft Rains as an echo of the house from Annie:

“Ten o'clock. The sun came out from behind the rain. The house stood alone in a city of rubble and ashes. This was the one house left standing. At night the ruined city gave off a radioactive glow which could be seen for miles… The water pelted window panes, running down the charred west side where the house had been burned, evenly free of its white paint.”

The role the house plays in Bradbury’s story, however, is more than just of a physical structure. Robotically, it continues to act out its programmed daily routine, chirpily running through the times of the morning schedule, “Eight-one, tick-tock, eight-one o'clock, off to school, off to work, run, run, eight-one!” As we see the house chiming off birthdays, preemptively preparing the correct amount of breakfast and reading a daily poem, we see the traces of its inhabitants. It becomes clear that it is more than just a structure; it is, as Gaston Bachelard puts it, “the topography of our intimate being”, a physical imprint of our metaphysical selves. Yet the inherent artificiality of the house’s intelligence turns what could be a continuation of life into satire. The elements of the machine continue to act out a version of ‘life’, woodenly delivering the same old lines, yet the purpose is gone. The last vestiges of non-artificial life in the form of the dying family dog ravaged by radiation are quickly cleaned away by the house, the inconvenient reality of life spoiling the carefully automated diorama. Yet even though it is artificial, the destruction of the home at the end of the story still feels like an extra cruelty. It feels as if the memory of the family is also being destroyed, not like the loss of a family member, but perhaps more like a missing photo album.

In nuclear fiction, an apocalypse doesn’t always mean total physical destruction. Many writers imagine worlds depopulated by fallout that remain physically pristine. The invisible and fatal fog can make whole areas of the earth uninhabitable yet leave the built structures totally intact. On The Beach by Nevil Shute takes place in just such a world. All but Australia has already been rendered uninhabitable and the residents of the former colony have just a few months to live. A submarine crew is sent to investigate an unknown radio signal in San Francisco, a potential sign of survivors. When they arrive the captain views the surrounding streets through the periscope, completely undamaged and bathed in sun.

The normality of the scene is broken by its total stillness, the lack of people, the cars eerie and unmoving. As observed by Richard Sennett, a sociologist at LSE, the modern city is much like Proust’s Paris, “assembled from his characters’ perceptions of the various shops, flats, streets and palaces” the city is an artefact of its creators, “a complex molecule of existence”. When the characters leave, it becomes like Bradbury’s house, a kind of cenotaph, with the lives and memories of its citizens echoed in the patterns of the streets and dirt.

To complete their mission a crew member is sent in a protective suit to investigate the signal. At a hydroelectric station he finds the source of the signal: a coke bottle caught in a flapping window shade. It jerks out meaningless monkey-with-typewriter morse code as it blows in the wind. The Coke bottle, portrayed in a painting by Warhol just five years later, puts a sharp twist on the legacy of the city. The viewer is left to reflect on the character and quality of the traces we leave, the good and the bad. For Shute it is the Coke bottle, the fading icons of a stale capitalism, for Bradbury it is the poems, selected at random from the archives of the house, “there will come soft rains and the smell of the ground…”. As much as home is the physical structure, any immigrant knows that home is culture more than anything. Perhaps during the Cold War this was more true than ever, the for-and-against propaganda war hyperbolised the Russo-American cultures to the point of pastiche. In the 1950s the white picket fence and shutters were so ever-present that the house from Annie was obviously a physical synonym for home. The smooth curves of the Hudson Hornet in the driveway behind it also says America (or perhaps more accurately ‘The West’) just as loudly. The cultural gravity is so large that although On The Beach claims to be set in Australia, the viewers immediately read the suburban prairie-style houses for what they are. As the panning camera takes in the horses in the carport instead of cars we note the glitch in the image of ‘home’ constructed by the US propaganda machine. In the main city, bicycles fill the streets instead of cars. Shute shows us in these small moments in which the nuclear apocalypse means the destruction not just of the physical home, but of the metaphysical one as well.

The cultural version of home has not proved as static as the physical. The scenes of bicycles replacing car traffic in the cities of On The Beach were designed to shock readers at the time and yet, to the modern eye, they appear almost utopian. The aftertaste of the American Dream turns out to be sour. This impression, starting as an undercurrent, becomes a significant strain of nuclear fiction. In Bradbury’s There Will Come Soft Rains, the counter-cultural voice is that of the Sara Teasdale poem for which the story is named.

“And not one will know of the war, not one

Will care at last when it is done.

Not one would mind, neither bird nor tree,

If mankind perished utterly;

And Spring herself, when she woke at dawn

Would scarcely know that we were gone.”

Though born out of the horrors of World War I, the lines still feel strikingly modern, fantasising about a post-human world that stands in stark contrast to the industrialised and mediated modernity of the home in the West. The post-car world of doomed Australia can just as easily be seen as transcendent as it can be as apocalyptic. As the end approaches, the characters refocus on the ‘important things in life’, returning to an earlier, more innocent existence.

“In Mary Holmes’ garden the first narcissus bloomed on the first day of August, the day the radio announced, with studied objectivity, cases of radiation sickness in Adelaide and Sydney. The news did not trouble her particularly; all news was bad, like wage demands, strikes, or war, and the wise person paid no attention to it. What was important was that it was a bright, sunny day; her first narcissus were in bloom, and the daffodils behind them were already showing flower buds.”

By questioning the western cultural ideal of home, nuclear fiction writers were opening the door to more explicitly critical writing that attempts to come to terms with the nuclear horror already inflicted by the West at the end of the war. In JG Ballard’s 1964 short story “The Terminal Beach”, a man journeys to Eniwetok, a Pacific atoll used by the Americans as a nuclear testing ground, and subsequently descends into madness among the scattered remains of the brutalist testing infrastructure.

“Despite the sand and the few anaemic palms, the entire landscape of the island was synthetic, a man-made artefact with all the associations of a vast system of derelict concrete motorways. Since the moratorium on atomic tests, the island had been abandoned by the Atomic Energy Commission, and the wilderness of weapons aisles, towers and blockhouses ruled out any attempt to return it to its natural state.”

By linking the architecture of utilitarian testing bunkers to the sprawling freeways of the West, Ballard draws the world of the apocalypse completely into our cultural conception of home. The atoll is portrayed as a machine for producing suburbia where the field of bunkers are like “the cutting faces of a gigantic dieplate, devised to stamp out rectilinear volumes of air the size of a house”. The American dream of picket fences and two cars in the driveway is inseparable from the nuclear research that coincides with it technologically and implicitly enables it. After this realisation, the entire conception of home as it had been idealised in the mid-20th century is soiled, driving Ballard’s lost character to this historical origin story, to discover what remains.

To complete their mission a crew member is sent in a protective suit to investigate the signal. At a hydroelectric station he finds the source of the signal: a coke bottle caught in a flapping window shade. It jerks out meaningless monkey-with-typewriter morse code as it blows in the wind. The Coke bottle, portrayed in a painting by Warhol just five years later, puts a sharp twist on the legacy of the city. The viewer is left to reflect on the character and quality of the traces we leave, the good and the bad. For Shute it is the Coke bottle, the fading icons of a stale capitalism, for Bradbury it is the poems, selected at random from the archives of the house, “there will come soft rains and the smell of the ground…”. As much as home is the physical structure, any immigrant knows that home is culture more than anything. Perhaps during the Cold War this was more true than ever, the for-and-against propaganda war hyperbolised the Russo-American cultures to the point of pastiche. In the 1950s the white picket fence and shutters were so ever-present that the house from Annie was obviously a physical synonym for home. The smooth curves of the Hudson Hornet in the driveway behind it also says America (or perhaps more accurately ‘The West’) just as loudly. The cultural gravity is so large that although On The Beach claims to be set in Australia, the viewers immediately read the suburban prairie-style houses for what they are. As the panning camera takes in the horses in the carport instead of cars we note the glitch in the image of ‘home’ constructed by the US propaganda machine. In the main city, bicycles fill the streets instead of cars. Shute shows us in these small moments in which the nuclear apocalypse means the destruction not just of the physical home, but of the metaphysical one as well.

The cultural version of home has not proved as static as the physical. The scenes of bicycles replacing car traffic in the cities of On The Beach were designed to shock readers at the time and yet, to the modern eye, they appear almost utopian. The aftertaste of the American Dream turns out to be sour. This impression, starting as an undercurrent, becomes a significant strain of nuclear fiction. In Bradbury’s There Will Come Soft Rains, the counter-cultural voice is that of the Sara Teasdale poem for which the story is named.

“And not one will know of the war, not one

Will care at last when it is done.

Not one would mind, neither bird nor tree,

If mankind perished utterly;

And Spring herself, when she woke at dawn

Would scarcely know that we were gone.”

Though born out of the horrors of World War I, the lines still feel strikingly modern, fantasising about a post-human world that stands in stark contrast to the industrialised and mediated modernity of the home in the West. The post-car world of doomed Australia can just as easily be seen as transcendent as it can be as apocalyptic. As the end approaches, the characters refocus on the ‘important things in life’, returning to an earlier, more innocent existence.

“In Mary Holmes’ garden the first narcissus bloomed on the first day of August, the day the radio announced, with studied objectivity, cases of radiation sickness in Adelaide and Sydney. The news did not trouble her particularly; all news was bad, like wage demands, strikes, or war, and the wise person paid no attention to it. What was important was that it was a bright, sunny day; her first narcissus were in bloom, and the daffodils behind them were already showing flower buds.”

By questioning the western cultural ideal of home, nuclear fiction writers were opening the door to more explicitly critical writing that attempts to come to terms with the nuclear horror already inflicted by the West at the end of the war. In JG Ballard’s 1964 short story “The Terminal Beach”, a man journeys to Eniwetok, a Pacific atoll used by the Americans as a nuclear testing ground, and subsequently descends into madness among the scattered remains of the brutalist testing infrastructure.

“Despite the sand and the few anaemic palms, the entire landscape of the island was synthetic, a man-made artefact with all the associations of a vast system of derelict concrete motorways. Since the moratorium on atomic tests, the island had been abandoned by the Atomic Energy Commission, and the wilderness of weapons aisles, towers and blockhouses ruled out any attempt to return it to its natural state.”

By linking the architecture of utilitarian testing bunkers to the sprawling freeways of the West, Ballard draws the world of the apocalypse completely into our cultural conception of home. The atoll is portrayed as a machine for producing suburbia where the field of bunkers are like “the cutting faces of a gigantic dieplate, devised to stamp out rectilinear volumes of air the size of a house”. The American dream of picket fences and two cars in the driveway is inseparable from the nuclear research that coincides with it technologically and implicitly enables it. After this realisation, the entire conception of home as it had been idealised in the mid-20th century is soiled, driving Ballard’s lost character to this historical origin story, to discover what remains.

Debora Greger’s writings from just after the end of the cold war, attempt to grapple more directly with this conflicted vision of home. Set in the world of the ‘90s Midwest, of ‘used car lots’ and “milk from the dairy”, where the vibrancy of Americana had long since faded, her poems are fuelled by an emotional struggle with the place. As a child of a scientist working in a nuclear lab near Hanford, Washington, her love for the place and the people is self-evident. The realisation in adulthood of the impact of the work, however, colours those memories and throws them into a new light. Her poem The Cloud of Unknowing, prefaced by the words “Hanford, Nagasaki”, wrestles with this tension:

“I should have lain in the dirt

looking up like the nun

who put a dark cloud between himself and his god,

the better to see him.

I should have been the woman looking up:

the waters of the sky parting,

only a few parachutes drifting low,

testing the wind.

And then the darkness covered the earth.”

The lines exude shame and, in her attempt to resolve the unfairness of experience between her city and theirs, she falls into a kind of masochism. Steeped in the language of religion and judgement, there is the feeling throughout these writings that perhaps home actually deserves its apocalypse.