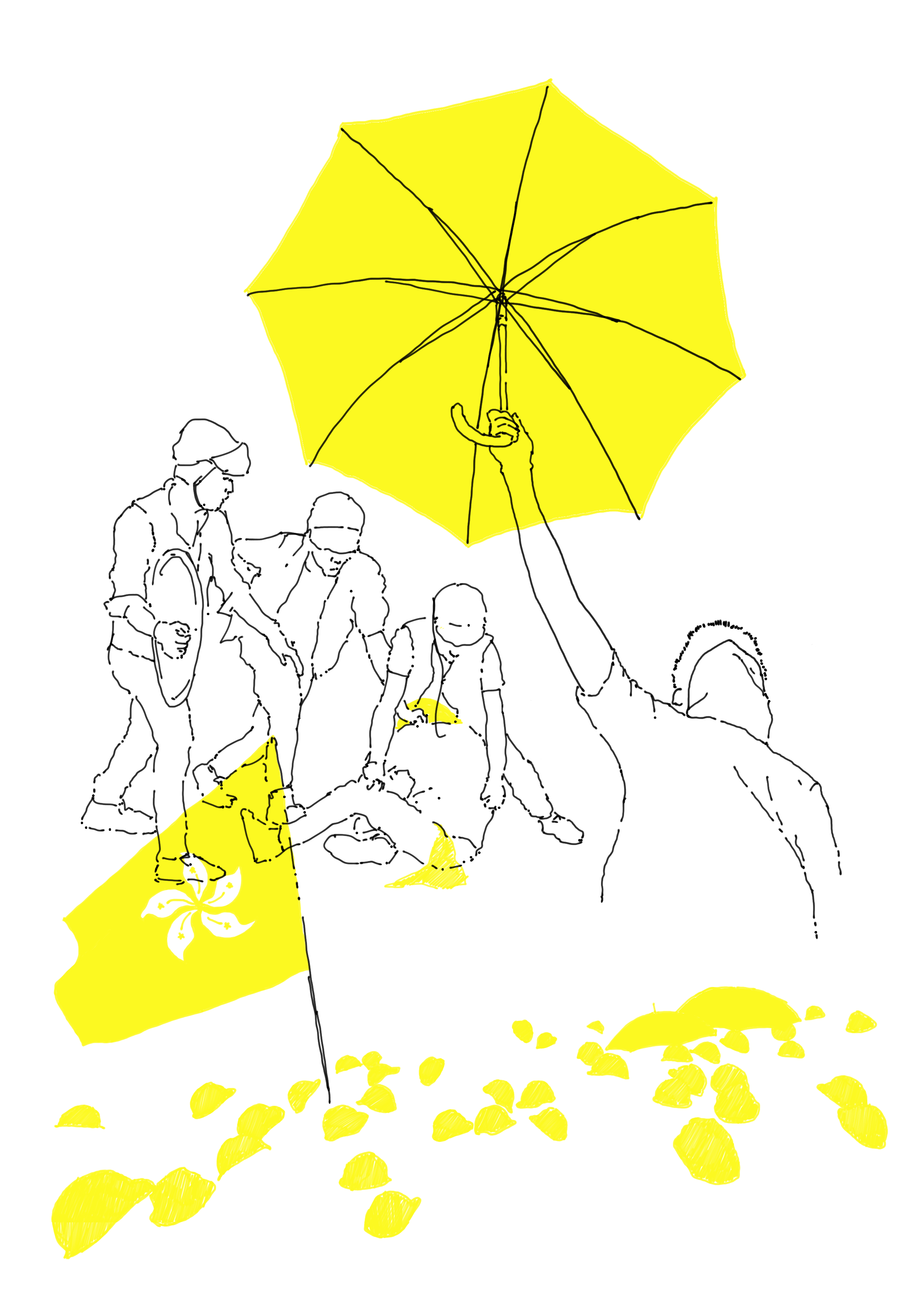

On the 9th of June 2019 over a million protesters took to the streets of Hong Kong to show opposition to the ‘Extradition Bill’. This controversial piece of legislature tabled before the Hong Kong parliament would give China the right to extradite Hong Kongers to mainland China to be tried in courts under direct party control. After a week of public fumbling and a second-reading blocked by public protest, the government agreed to suspend the bill but did not fully withdraw it from the legislature. In response to this attempt to placate the opposition, on June 16th a second public action took over the city. From a total population of seven million people nearly two million walked out in protest. Families attended together, fathers marched with children on their shoulders, yet despite the demonstrations the government continued to refuse to fully withdraw the extradition bill.

Protest and activism have re-entered public consciousness in Hong Kong. Worldwide, the mass protests of the 2010s have frequently reached numbers unseen since the great civil actions of the late 1900s. Despite resistance and foot-dragging from the architectural establishment, the ongoing protests have opened a discussion about architecture’s role in creating democratic public space and perhaps even shaping politics. This re-examination of past decisions by architects and city planners has foregrounded the political nature of the built environment, shining fresh light on the city’s values.

Unrest over the public realm is not a modern phenomenon in Hong Kong. In the early, intensely overcrowded conditions of a racially segregated Hong Kong, private activities that could find no place in the shophouse-tenements often bled out on to the streets. The ‘five foot way’ became a new kind of space across the boundary between public and private that ran counter to the colonial imperial logic of streets-and-dwellings. Attempts to control the use of this mandated walkway culminated in riots in 18881 that saw the city brought to a complete stand-still. Today, despite protesters retaking Hong Kong in huge numbers every night - disrupting routes with traffic cones and bits of metal fence - the better-equipped and armoured police can clear them out relatively easily. As layered intricacy of the old city has been replaced by the sleek smoothness of modernity the small footholds that might have allow protestors to resist have disappeared. By the early morning the road sweepers have come out with backhoes to clear the barricades and remove the graffiti. The previous day’s protests are almost invisible to the city executives arriving for work the next morning. It would appear the city has designed out lasting protest.

Two weeks after the march on June 15th, another pro-democracy demonstration again drew record numbers. During a day of marches marking the 1997 handover of Hong Kong to China, a group assembled around the LegCo (the Hong Kong Legislative Council) and began to use a trolley and pieces of scrap metal to batter the glass doors and security gates. By nightfall, after 9 hours of battering, the security walls finally gave in and protesters stormed the legislative chamber. Inside, they graffitied the walls with pro-democracy slogans and replaced the flag with the movement’s colours. Occupying the architectural manifestation of political will in Hong Kong, they held their position for two whole hours whilst reading out their demands to the assembled media.

Protest and activism have re-entered public consciousness in Hong Kong. Worldwide, the mass protests of the 2010s have frequently reached numbers unseen since the great civil actions of the late 1900s. Despite resistance and foot-dragging from the architectural establishment, the ongoing protests have opened a discussion about architecture’s role in creating democratic public space and perhaps even shaping politics. This re-examination of past decisions by architects and city planners has foregrounded the political nature of the built environment, shining fresh light on the city’s values.

Unrest over the public realm is not a modern phenomenon in Hong Kong. In the early, intensely overcrowded conditions of a racially segregated Hong Kong, private activities that could find no place in the shophouse-tenements often bled out on to the streets. The ‘five foot way’ became a new kind of space across the boundary between public and private that ran counter to the colonial imperial logic of streets-and-dwellings. Attempts to control the use of this mandated walkway culminated in riots in 18881 that saw the city brought to a complete stand-still. Today, despite protesters retaking Hong Kong in huge numbers every night - disrupting routes with traffic cones and bits of metal fence - the better-equipped and armoured police can clear them out relatively easily. As layered intricacy of the old city has been replaced by the sleek smoothness of modernity the small footholds that might have allow protestors to resist have disappeared. By the early morning the road sweepers have come out with backhoes to clear the barricades and remove the graffiti. The previous day’s protests are almost invisible to the city executives arriving for work the next morning. It would appear the city has designed out lasting protest.

Two weeks after the march on June 15th, another pro-democracy demonstration again drew record numbers. During a day of marches marking the 1997 handover of Hong Kong to China, a group assembled around the LegCo (the Hong Kong Legislative Council) and began to use a trolley and pieces of scrap metal to batter the glass doors and security gates. By nightfall, after 9 hours of battering, the security walls finally gave in and protesters stormed the legislative chamber. Inside, they graffitied the walls with pro-democracy slogans and replaced the flag with the movement’s colours. Occupying the architectural manifestation of political will in Hong Kong, they held their position for two whole hours whilst reading out their demands to the assembled media.

While public spaces in Hong Kong seem to have been extensively riot-proofed, architects and the governments that employ them still seek to create government buildings that communicate the democratic values they claim to uphold. The broadly circular legislative chamber of Hong Kong’s LegCo suggests a collaborative and cross-party approach to governance, more akin to the egalitarian models of countries like Germany and Sweden than the partisan opposing benches of the Westminister.

Yet with only half the LegCo seats directly elected by the public and the selection of the Chief Executive by Election Committee rather than by public vote, this architecture is more value-camouflage than a genuine tool for democracy.

The democratic signalling continues outside of the chamber itself. At LegCo, a large public park slides through the centre of the complex leading up from a water-side promenade. This enormous political space is ringed by glass walls that speak a language of transparency and openness. The plaza feels as if the public who use it could converse directly with the political actors who represent them. This is a feeling not shared by the protesters who shattered that illusion of transparency. The architectural game was up, and the building relented to the force of the protests that refused to believe the symbol sold at the seat of the government.

In light of the recent protests, the symbolism embodied in the architecture of the LegCo seems worryingly shallow and the street forms that stifle demonstration seem all too efficient. The language of the city has little time for protesters. Yet, despite the heavy odds stacked against them, Hong Kong’s resistance is learning to leverage unwitting elements of the modern built environment in its interest.

In lieu of old-city alleyways the shopping mall has now become the venue for guerilla protest. The many routes in to and out of the building - designed to maximise frontage - now allow for effective micro-protesting. Groups of activists can assemble quickly in large atria for maximum public exposure singing their call-to-arms rallies before diffusing along good public transport links. Aside from capturing the LegCo, activists have also started to occupy other public buildings. The post 9-11 design regulations for tightly controlled entrance points in structures such as university libraries and halls of residence have created fortresses for those without police power. Control over the entrance of a building on the CUHK campus allowed students to occupy the space for a week, using it as a base of operations to block the highway below. Despite the changing city, the movement evolves and the protest continues.

The most recent protests in Hong Kong have revealed Architects as poor stewards of the democratic city. However, after seven months of unrest, architecture’s complicity in attempts to control political action luckily seem to have failed. Yet by learning from the new tactics of the modern urban protester, architects can still have an impact on the future of bottom-up civic actions. In order to make the city a more hospitable place for democracy the profession should be watching the protests with a keen eye.

The democratic signalling continues outside of the chamber itself. At LegCo, a large public park slides through the centre of the complex leading up from a water-side promenade. This enormous political space is ringed by glass walls that speak a language of transparency and openness. The plaza feels as if the public who use it could converse directly with the political actors who represent them. This is a feeling not shared by the protesters who shattered that illusion of transparency. The architectural game was up, and the building relented to the force of the protests that refused to believe the symbol sold at the seat of the government.

In light of the recent protests, the symbolism embodied in the architecture of the LegCo seems worryingly shallow and the street forms that stifle demonstration seem all too efficient. The language of the city has little time for protesters. Yet, despite the heavy odds stacked against them, Hong Kong’s resistance is learning to leverage unwitting elements of the modern built environment in its interest.

In lieu of old-city alleyways the shopping mall has now become the venue for guerilla protest. The many routes in to and out of the building - designed to maximise frontage - now allow for effective micro-protesting. Groups of activists can assemble quickly in large atria for maximum public exposure singing their call-to-arms rallies before diffusing along good public transport links. Aside from capturing the LegCo, activists have also started to occupy other public buildings. The post 9-11 design regulations for tightly controlled entrance points in structures such as university libraries and halls of residence have created fortresses for those without police power. Control over the entrance of a building on the CUHK campus allowed students to occupy the space for a week, using it as a base of operations to block the highway below. Despite the changing city, the movement evolves and the protest continues.

The most recent protests in Hong Kong have revealed Architects as poor stewards of the democratic city. However, after seven months of unrest, architecture’s complicity in attempts to control political action luckily seem to have failed. Yet by learning from the new tactics of the modern urban protester, architects can still have an impact on the future of bottom-up civic actions. In order to make the city a more hospitable place for democracy the profession should be watching the protests with a keen eye.